Espresso crops are dying from a fungus with species-jumping genes – researchers are ‘resurrecting’ their genomes to grasp how and why

For anyone who relies on coffee to start their day, coffee wilt disease may be the most important disease you’ve never heard of. This fungal disease has repeatedly reshaped the global coffee supply over the past century, with consequences that reach from African farms to cafe counters worldwide.

Infection with the fungus Fusarium xylarioides results in a characteristic “wilt” in coffee plants by blocking and reducing the plant’s ability to transport water. This blockage eventually kills the plant.

Some of the most destructive plant pathogens in the world infect their hosts in this way. Since the 1990s, outbreaks of coffee wilt have cost over US$1 billion, forced countless farms to close and caused dramatic drops in national coffee production. In Uganda, one of Africa’s largest producers, coffee production did not recover to pre-outbreak levels until 2020, decades after coffee wilt was first detected there. And in 2023, researchers found evidence that coffee wilt disease had resurfaced across all coffee-producing regions of Ivory Coast.

Studying the genetics of plant pathogens is crucial to understanding why this disease continues to return and how to prevent another major outbreak.

Rise and fall of coffee wilt disease in Africa

While early outbreaks of coffee wilt disease affected a wide range of coffee types, later epidemics primarily affected the two coffee species dominating global markets today: arabica and robusta.

First identified in 1927, coffee wilt disease decimated several varieties of coffee grown in western and central Africa. Although farmers combated the fungus with a shift to supposedly resistant robusta crops in the 1950s, the reprieve was short-lived.

The disease reemerged in the 1970s on robusta coffee, spreading through eastern and central Africa. By the mid-1990s, yields had collapsed and coffee production could not recover in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Separately, researchers identified the disease on arabica coffee in Ethiopia in the 1950s and watched it become widespread by the 1970s

Peck et al 2023/Plant Pathology, CC BY-SA

Although coffee wilt disease is currently endemic at low and manageable levels across eastern and central Africa, any future resurgence of the disease could be catastrophic for African coffee production. Coffee wilt also poses a threat to producers in Asia and the Americas.

New types of disease emerge

Coffee wilt disease evolved alongside coffee itself. Over the past century, it has repeatedly reemerged, attacking different types of coffee each time. But did these shifts reflect the rapid evolution of new types of disease, or something else entirely?

Fungal disease has devastated plants for millennia, with the earliest records of outbreaks dating from the biblical plagues. Like humans, plants have an immune system that protects them against attacks from pathogens like fungi.

While most fungal attempts at infection fail, a small number do succeed thanks to the constant evolutionary pressure on pathogens to overcome host plant defenses. In this evolutionary arms race, pathogens and hosts continuously adapt to each other by genetically changing their DNA. Boom and bust cycles of disease occur as one gains advantage over the other.

The rise of modern agriculture has led to widespread monocultures of genetically uniform crops. While monocultures have significantly boosted food production, they have also contributed to environmental degradation and increased plant vulnerability to disease.

Crop breeders have attempted to protect monocultures by introducing disease resistance genes, with farms widely applying fungicides and other environmentally damaging products. But these relatively weak protections for hundreds of acres of identical plants have resulted in outbreaks decimating crops that people depend on.

It’s likely that modern agriculture’s reliance on monocultures has enabled and accelerated the evolution of new types of pathogen capable of overcoming resistance in plants. As a result, crops become more susceptible to disease outbreaks.

Resurrecting fungal strains

Understanding the lessons of the past is essential to avoiding future plant pandemics. But this can be challenging, because the specific pathogen strains that caused previous disease outbreaks may no longer exist in nature or may have changed substantially.

In my research on the evolutionary arms race between host and pathogen in coffee wilt disease, I sought to address these problems by “resurrecting” historical strains of the fungus that causes the disease, Fusarium xylarioides. Researchers know little about why the earlier and later outbreaks targeted different types of coffee, so I explored the genetic changes in F. xylarioides that underlie this narrowing of its hosts.

I reconstructed historical genetic changes in the major coffee wilt disease outbreaks over the past seven decades by using strains from a fungus library – culture collections that preserve living fungi. These libraries store long-term living data and reflect the fungal genetic diversity present at the time of collection.

Julie Flood

Whether a pathogen takes the upper hand in the evolutionary arms race depends on its ability to generate new types of genes. It can do so either by changing and rearranging its DNA sequence or by moving DNA sequences between organisms in a process called horizontal gene transfer. These mechanisms can create new effector genes that enable pathogens to infect and colonize a host plant.

Initially, I sequenced six whole genomes of strains involved in outbreaks before the 1970s as well as later outbreaks that specifically targeted arabica or robusta coffee plants. I found that strains of F. xylarioides specific to arabica or robusta genetically differed from each other, with most of these differences inherited from parent to offspring. This process is called vertical inheritance.

Genes that jump between species

However, I also found that several regions of the F. xylarioides genome were potentially acquired horizontally from F. oxysporum, a global plant pathogen that infects over 120 crops, including bananas and tomatoes. These included different regions of the genome across strains specific to arabica and robusta coffee.

But did these changes introduce new effector genes in the F. xylarioides strains that infect arabica and robusta coffee plants specifically? To answer this question, I first sequenced and assembled the first F. xylarioides reference genome, stitching together long stretches of DNA. I then sequenced and compared this reference genome to the whole genomes of three more pre-1970s F. xylarioides strains and 10 additional historical Fusarium strains found on or around diseased coffee bushes, as well as F. xylarioides strains from infected arabica coffee seedlings.

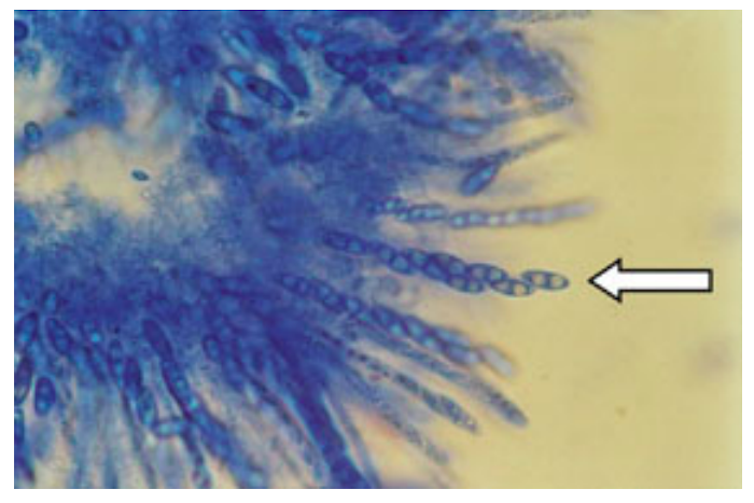

I found substantial evidence for horizontal transfer of disease-causing genes between species of Fusarium. This includes the presence of giant genetic components called Starships in Fusarium. These so-called jumping genes carry their own molecular machinery, allowing them to move around or between genomes. Genes involved in adaptation, such as those linked to virulence, metabolism or host interaction, also move with them. Scientists think Starships may potentially enable fungi to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

I found that large and highly similar genetic regions, including Starships and active effector genes involved in disease, had moved from F. oxysporum to F. xylarioides. Importantly, different genetic regions were present across strains of F. xylarioides specific to arabica and robusta, but they were absent from other related Fusarium species. This suggests that these genes were gained from F. oxysporum.

Arming farmers with knowledge

Today, a third of all global crop yields are lost to pest and disease. Reconciling the tension between agricultural productivity and environmental protection is important to balance humanity’s needs for the future. Central to this challenge is reducing the spread of disease and new outbreaks.

On the flip side to monocultures, many plant species surrounding and within small and family-run coffee farms in sub-Saharan Africa may act as disease reservoirs, where fungi pathogens can lurk. These include banana trees and Solanum weeds in the tomato family that are susceptible to fungal infection.

Human farming practices may have inadvertently created an artificial niche for these fungi, with coffee bushes brought into widespread contact with banana plants and Solanum weeds. If fungi in the same genus can frequently exchange genetic material, it could accelerate the ability of plant pathogens to adapt to new hosts.

Wayne Hutchinson/Farm Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Testing noncoffee plants for F. xylarioides infection could reveal alternative plant species where different Fusarium fungi come into contact and exchange genetic material. This matters because across sub-Saharan Africa, coffee plants often share fields with banana trees and weeds. If these neighboring plants can harbor fungi that act as new sources of genetic variation, they may help fuel new disease strains.

Identifying the plants that can act as hosts to fungi could give farmers practical options to reduce coffee plants’ risk of disease, from targeted weed management to avoiding the planting of vulnerable crops side by side.