Grasp Plan To Islamize Hispaniola Island – JP

Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Truth Social, Gettr, Twitter, Youtube

Edited by Eduardo Vidal

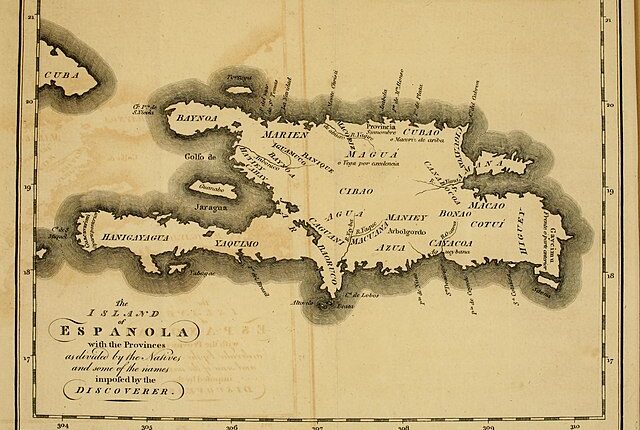

Dominican Republic — Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic, is under what some describe as an Islamic push. There’s a surge in mosque construction, a flood of Haitian migrants crossing into the DR, and whispers of a broader plan to shift the island’s Roman Catholic culture. Some say it’s orchestrated. Others call it chaos. Here’s the story, plain and simple.

The Migration Wave: Accident or Strategy?

Haiti is collapsing. Gangs control most of Port-au-Prince. More than 5,600 people were killed in 2024, over a million are displaced, and tens of thousands are crossing the 224-mile border into the Dominican Republic.

Estimates say between 700,000 and 1 million Haitians now live in the DR — as much as 25% of the workforce in construction, farming and tourism. President Luis Abinader has responded by building a border wall, deploying 1,500 agents, and deporting 119,000 people in early 2025. Yet the flow continues. Human rights groups call the raids harsh — with reports of pregnant women and children detained in hospitals and schools.

But online, many wonder: Is this migration being pushed on purpose? Some point to Turkish NGOs, Persian Gulf funding, and local Arab businessmen. They claim that aid from mosques in Haiti lures migrants with promises of jobs and safety in the DR — only to settle them near new mosques, such as the large one in Punta Cana. It’s being called a “soft invasion.” There’s no hard proof, but even the U.S. State Department has warned of “uncontrollable migration waves.”

Fake IDs: A Quiet Takeover?

Here’s where it gets murkier. The DR has deported over 1.1 million irregular migrants since 2016, but reports indicate that many Haitians are obtaining fake Dominican IDs and even passports — sometimes for $1,000 to $2,000 through corrupt officials or Arab-linked networks. A 2025 bust exposed a forgery ring charging up to $27,000 per client, using routes through Haiti and Venezuela. Authorities seized fake passports and 1,500 government stamps.

Haiti’s own ID system is in disarray — only 4.4 million of its 12 million citizens are registered — making forgery easier. Critics warn that the pattern is clear:

Give migrants IDs → enroll them in free ;ublic services → increase their numbers → gain political power → erode the DR’s Roman Catholic identity.

Free Services, Full Hospitals, Empty Budget

The strain is real. In 2023, Haitian mothers accounted for 40% of all births in Dominican public hospitals — and up to 80% in border areas. This costs the DR millions annually. Over 80,000 Haitian children have enrolled in Dominican public schools in the past four years.

Dominicans often wait months for surgeries, while undocumented migrants receive emergency care immediately — all funded by Dominican taxpayers. President Abinader has proposed charging foreigners for public services, but hospital raids that detained pregnant women sparked outrage. On social media, anger is rising: “Why do we pay for their healthcare while our own people suffer?”

Some tie the issue to mosque growth: once settled, migrant families send their children to Islamic schools. Observers fear that if unrest spreads, the DR’s $9 billion tourism industry — sustained largely by American visitors — could collapse.

The Bigger Picture: A Plan to Change the Island?

Put it all together:

• Flood the DR with Haitian migrants;

• Give them IDs;

• Let them use public services;

• Build mosques; and

• Shift the culture.

Haiti faces a spiritual void as Vodou declines, while the DR remains about 95% Roman Catholic. Some fear that a “critical mass” of Muslims could push for Sharia-influenced communities.

Arab elites reportedly control 70% of the DR’s trade. They have money, influence, and connections — even within the presidency.

Who’s Really in Charge?

President Luis Abinader is of Lebanese Christian descent, as is his wife. Critics claim his Arab ties make him lenient toward mosque expansion and migration.

Then there’s Gilbert Bigio — Haiti’s richest man, of Jewish-Haitian and Syrian heritage. His GB Group dominates steel, telecom and fuel across the Caribbean. He purchased Chevron’s gas stations in the DR, and his company’s CEO, Pablo Daniel Portes Goris, is a presidential advisor.

Canada sanctioned Mr. Bigio in 2022 for allegedly arming gangs and laundering money. Yet President Abinader did not bar him from operating in the DR. Bigio’s fuel empire profits from smuggling cheap Dominican gasoline into Haiti’s black market — and, some allege, indirectly into Hezbollah or HAMAS-linked networks.

Fuel, Drugs, and Extremism

Fuel smuggling is rampant. Gasoline sells for about $5 per gallon in the DR but up to $50 on Haiti’s black market. Motorcycles, boats and hidden routes transport it. One bust seized 2,700 gallons.

The smuggling networks connect to Cuba and Venezuela — and intelligence sources whisper about Hezbollah and HAMAS involvement. The U.S. Treasury has linked certain Venezuelan gangs to money laundering operations near DR routes.

Drug trafficking adds to the chaos: over 30 tons of cocaine were seized in the DR in 2025 alone, marking a record year. The island serves as a key corridor from Colombia to the U.S. and Europe. Gangs, drugs, fuel and migration feed one another — creating a perfect storm.

Enter Ambassador Leah F. Campos

Recently confirmed in October 2025, Ambassador Leah F. Campos — a former CIA officer fluent in Spanish — now leads the U.S. mission in the DR. Her priorities include:

• Strengthening U.S.–Dominican cooperation on border security,

• Combating crime and transnational cartels,

• Disrupting fuel smuggling and sanctioning corrupt elites, and

• Countering Chinese influence in the region.

Her arrival signals a tougher U.S. stance on regional instability.

The Bottom Line

This isn’t just about migration or mosques. It’s about who controls Hispaniola — its culture, its economy, and its future.

Fuel the gangs → flood the borders → build the mosques → change the soul of the island.

The U.S. and the Dominican Republic are fighting back — but time is running out. Stay alert. This story isn’t over.