Yes, Google is a near-monopoly, but selling off Chrome won’t make it better

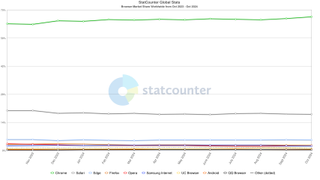

Google’s Chrome browser is dominant; not in the way Google’s search engine is, but at 67% market share, according to Stat Counter, it sits comfortably atop competitors like Safari, Edge, and Opera, who are mostly fighting over scraps.

For the US Government, which is now calling for the breakup of Google by having it sell off Chrome and, perhaps, Android, it’s not so much the market share that matters as much as how Chrome acts as a powerful fulcrum for Google’s other interests, chief among which is maximizing advertising revenue.

Here’s how it works. Chrome is a web browser like Safari and others, but it’s also a search engine interface. The default search engine when Chrome is delivered to your desktop or smartphone is, naturally, Google. These days there are few people who only type websites into their browser address bar (so-called because we were only supposed to put the ‘address’ or URL for our desired website in there). Now we use our browser address bars as prompt fields. That’s right; long before the advent of AI, we were typing in fully-formed sentences and, invariably, getting canny answers from Google’s powerful search engine.

I’ve argued here and elsewhere that Google’s search dominance comes by way of quality not coercion.

That’s not all we’ve been getting. If I type, “Where do I find the best mattresses?” into my Chrome address bar, Google Search instantly returns a page of results. ‘Sponsored’ links occupy, by my estimate, 95% of the desktop web page results. I have to scroll down to perhaps the fourth result to see some suggestions from The New York Times.

Google gets paid for those ads; and, essentially every time you search, for every result with ads, Google gets a cut. If Google isn’t serving partner ads, then it has ads delivered in search and through millions of websites by its own Doubleclick ad network. It’s a system that barters and then fills countless bits of unsold inventory (pages where a specific advertiser didn’t choose to sponsor the site or page) to the highest-bidding advertiser. Google gets paid here, too (as do publishers).

The everything of Google

Even if you’re not on Chrome, Google search is pervasive. The search company pays Apple up to $20 billion a year to be the default search engine in Safari’s address bar.

If you own an Android phone, Chrome is often the default browser, or it’s at least pre-installed, and virtually all phones also feature Google Discover, which you can usually find by swiping right on your Android homepage. This feed is full of news and ads, with Google again getting paid for the latter.

Google’s reach and, perhaps, control, are undeniable. Is it a monopoly? A US federal judge said yes in August. I’ve argued here, and elsewhere, that Google’s search dominance comes by way of quality not coercion. Google entered a crowded search market and later a browser market dominated mostly by Microsoft and Internet Explorer. None of these competitors rolled over. Google just did it better.

Technology has a habit of choosing winners and losers. It’s also the nature of the beast to start demanding standards and uniformity. If there were two dozen operating systems across our desktops and mobile phones, developers would strain and probably break trying to support them all. In fact, they wouldn’t do it; and they, along with consumers, would soon pick the winners and losers.

Google in control

Google is not blameless here. It’s hard to deny the power and control that dominating market share gives you, and while consumers might initially choose a laptop manufacturer and a platform, it’s ultimately the tech companies like Google that lead and make decisions for us. They choose how the platforms will work, and which third-party systems to invite. They’re the ones connecting the dots on the back end – and that again is a considered decision that’s usually hidden from our view.

Chrome is not just a web browser; it’s an ecosystem, a platform inside platforms that we live and work in. I manage multiple email accounts, edit documents in Google docs, manage my photo library, post on social media, and, lately, conduct AI conversations all inside of Chrome, with every action and interaction passing by Google’s unblinking eye.

I’m not complaining. Google Search is still the best search engine in the business, and Chrome is an excellent browser that is finally getting its resource-hogging issues under control. It still earns its place on my desktop.

Will I be served by someone else owning Chrome and then taking the code in a different direction, perhaps away from its tight integration with the Google corpus? I don’t think so. I know Google definitely doesn’t think so. In a tersely worded response to the DoJ brief proposing the break-up, Kent Walker, Google & Alphabet President, Global Affairs & Chief Legal Officer, wrote:

“DoJ’s approach would result in unprecedented government overreach that would harm American consumers, developers, and small businesses – and jeopardize America’s global economic and technological leadership at precisely the moment it’s needed most.”

He added that it would hobble access to Google Search, endanger consumer privacy, and harm Google’s investment in AI.

Handicapping Google

Google is on the precipice of radically reimagining our search with deeper integration of AI overviews, Gemini-powered generative results that may soon overtake traditional Google Search results. Again, since Chrome is our de facto search prompt window, shifting the browser to another company means that it could be any AI that returns a result.

Google’s AI is not necessarily the best, yet, but it’s in a strong competitive position against, for instance, OpenAI and ChatGPT. I like how these companies are pushing each other. A Google breakup won’t help the race, or put the US in a better position relative to the rest of the world when it comes to AI development.

I also, ultimately, don’t want anyone to pull Google Search out of my Chrome. It’s a marriage I like, and one that works for me and, I bet, billions of others. Pulling them apart may make Google look less like a monopoly, but it won’t improve anyone’s life. I’d prefer that the DoJ and others focus on Google’s ad business and SEO control – there may be some more sensible remedies there.

I don’t know what will happen next. Google is now been labeled a monopoly, and the DoJ is calling for a breakup that could even include Android. But the X-factor here is that we are about to see a new administration in the White House, and changes at the top of the DOJ. Those changes could mean this initiative is killed off, or they could mean it’s accelerated; it could go either way, and your guess is as good as mine. Maybe ask Google Chrome – I’m sure it has the answers.